I'd just shipped the first release of a side project. Feeling productive, I immediately started setting up changesets, release automation, and versioning infrastructure. Then I paused. This project had one contributor (me), zero users, and exactly one release. Why was I adding release tooling designed for teams managing dozens of packages?

This happens a lot when you work alone. There's no one to say "do we actually need this?" So I built a Claude Code skill to be that voice.

The Problem

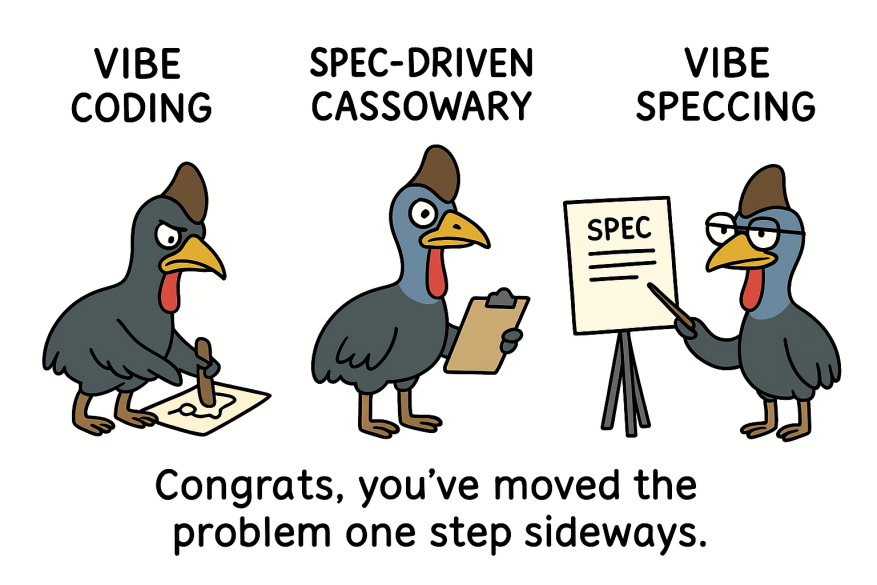

Solo developers don't have the natural friction that teams provide. On a team, proposing a new tool or architectural pattern means writing a proposal, getting feedback, defending the complexity. Working alone, you skip straight from "I heard about X" to npm install X. The gap between impulse and implementation is dangerously short.

I wanted something that would slow me down just enough to think clearly - without the overhead of a full team RFC process.

How I Built It

Claude Code skills are modular packages that extend Claude's capabilities with specialised knowledge and workflows. A skill is essentially a SKILL.md file (with YAML frontmatter and markdown instructions) plus optional reference files.

I used the Anthropics skill-creator to guide Claude Code to create an effective skill, giving it context of an RFC process I'd written up before and a prompt describing the skill I wanted to create. This created two files:

SKILL.md - The main skill definition with a 4-stage workflow:

- Problem Framing - Forces you to articulate the actual problem before discussing solutions. Asks pointed questions: "What happens if you do nothing for 3-6 months?"

- Research & Options - Explores your actual codebase first, then builds an honest comparison. Always includes "do nothing" as Option A.

- Decision - Applies a complexity filter: "Is this the simplest thing that could work at your current scale?"

- Document - Writes a lightweight RFC to

docs/decisions/as a persistent record.

references/rfc-template.md - A stripped-down decision document template with sections for: Summary, Problem, Options Considered, Decision, Rationale, and Next Steps.

The skill triggers automatically when you say things like "should I add X?", "is this overkill?", or "do I need Y?" - exactly the moments where premature complexity creeps in.

The key design decisions were:

- "Do nothing" is always an option. This is the core mechanism. Describing what "do nothing" actually looks like in practice reveals it's rarely as bad as you assumed.

- Codebase-aware. Stage 2 explores your actual project before researching solutions, grounding the discussion in reality rather than hypotheticals.

- Produces a decision record. Even if the decision is "do nothing," documenting why is valuable when you revisit the question six months later.

Local install

To install it for my user across all Claude Code sessions, I copied the skill directory to ~/.claude/skills/solo-rfc/.

Publishing to Tessl

If you want to share a skill beyond your own machine, you can publish it to the Tessl registry:

# creates the tile.json manifest file

tessl skill import ./solo-rfc --workspace nickrowlandocom

tessl skill publish --workspace nickrowlandocom ./skills/solo-rfc

The import tool will ask "Should the tile be public?". Selecting yes will set the private flag to false in the tile.json manifest file. This flag will make it discoverable by anyone, or keep it private to your workspace.

Publishing gives you:

- Discoverability - Others can find and install your skill from the registry with

tessl skill install - Versioning - Proper semantic versioning so consumers can pin to stable releases

- Distribution - Team members in your workspace get access automatically; public skills are available to the entire community

- Validation - Published skills are automatically linted and evaluated

For a skill like this, publishing publicly means any solo developer using Claude Code can benefit from the same "slow down and think" workflow - without building it themselves. I've published the solo-rfc skill — you can find it on the Tessl registry.